this blog has moved to

site moved

29 Thursday Dec 2022

Posted in Uncategorized

29 Thursday Dec 2022

Posted in Uncategorized

this blog has moved to

07 Monday Nov 2022

Posted in Christian ethics, pacifism, peace

The Lord loves those who hate evil;

Psalm 97:10 (Revised Standard Version)

he preserves the lives of his saints;

he delivers them from the hand of the wicked.

John Calvin’s Commentaries contain many hidden gems. Consider this almost pacifist interpretation of this passage:

As the persecution of the wicked is apt to provoke us to seek revenge, and unwarrantable methods of escape, the Psalmist guards us against this temptation, by asserting that God is the keeper and protector of his people. If persuaded of being under the Divine guardianship, we will not strive with the wicked, nor retaliate injury upon those who have wronged us, but commit our safety to him who will faithfully defend it. This gracious act of condescension, by which God takes us under his care, should serve as a check to any impatience we might feel in abstaining from what is evil, and preserving the course of integrity under provocation.

https://ccel.org/ccel/calvin/calcom11/calcom11.vi.iii.html

04 Friday Nov 2022

Posted in Christian ethics, peace, war

In the following paragraph the theologian Duncan Forrester explains how just war thinking is ethical and has become divorced from theological reflection:

Just war theory is a way of thinking which has its roots in pre-Christian classical philosophy and Christian metaphysics. It is ethical rather than theological, and precisely because it does not presuppose any religious commitment or involve an explicit dogmatic element it often commends itself as peculiarly appropriate in a secular age. But for centuries just war thinking was conducted within the theological framework, and when it is detached from that framework it becomes liable to subtle but significant modification. The theological frame affirmed that war and violence call for repentance and need forgiveness, despite the fact that in a fallen world we must expect conflict to take place. Thus the Norman knights who triumphed at the Battle of Hastings in a cause that had been declared just by the Pope himself were still required to do penance for having shed human blood. Just war considerations were used to discourage recourse to violence (ius ad bellum) and to promote restraint in the conduct of war (ius in bello) within the general theological assumption that all participation in war is sinful. The greater the distance that developed between the theology of war and the ethics of the just war the easier it became to regard war as sometimes good, or even holy, rather than always inherently sinful. As just war theory was increasingly detached from classical Christian theology and grafted on to a modern, more optimistic view of human nature and the world, it could offer little effective resistance to the acceptance or glorification of war which springs from seeing the modern ideological war as a Manichean confrontation of absolute good and absolute evil. A theory once intended to express an abhorrence of war often became a means of justifying it.

From: Duncan B. Forrester, ‘The Theological Task’, in Ethics and Defence: Power and Responsibility in the Nuclear Age, ed. Howard Davis (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986), 31–32. Reprinted as Duncan B. Forrester, ‘The Theological Task’, in Forrester on Christian Ethics and Practical Theology: Collected Writings on Christianity, India, and the Social Order, Ashgate Contemporary Thinkers on Religion: Collected Works (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 358–59.

This implies that Christian thinking about war can take place within a theological framework and that in doing so we can recapture a fuller picture of war and peace than a merely ethical one. To place the problem of war within theology opens up new discussions about the problem of war and the promotion of peace. This is theological work worth pursuing and worth funding.

20 Thursday Oct 2022

Posted in anarchism, Christian Anarchism

I co-coordinate the Cambridge Religious Anarchism Reading Group in Cambridge, UK.

The focus of this reading group is to read and discuss a range of anarchistic religious texts. The aim is to familiarize ourselves with the minority traditions of anarchism within religious traditions, their inspiration, sources, and their ongoing political and religious importance. Readings will include classic and modern texts, research papers in progress, and possibly new translations. All readers of good will are most welcome.

For more information see: https://rd652.notion.site/Cambridge-Religious-Anarchism-Reading-Group-564bb5f95b444f6092c553fe8bf7f280

07 Wednesday Sep 2022

Posted in climate change, Fiji, theology

Tags

A brief note to remind readers of my paper on Luther and climate change in the Pacific, but with application elsewhere. Available here:

‘Climate Justice and God’s Justice in the Pacific: Climate Change Adaptation and Martin Luther’

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-67602-5_6

Climate change activism in the Pacific is often narrated through the concept of justice. It is unjust, it is claimed, that the small island developing states of the Pacific should face so much harm and even eradication from the effects of climate change when they have contributed so little to global carbon emissions. This is an issue of climate justice. Yet islanders, who are mostly Christian, often narrate the effects of the climate change through the concept of God’s justice and judgement. In their disaster-prone region on the Pacific rim of fire, with tropical cyclones, tsunamis, and the threat of sea-level rise and coastal erosion, disasters invariably carry religious meaning. This alternative narrative can affect climate change adaptation for several reasons, including the idea that fighting climate change is fighting God’s judgement, which must be humbly accepted. And of what use are fortifications against sea-level rise, if God is judging you? To shed light on these issues from a theological angle, the chapter engages with the medieval theologian Martin Luther and how he understood the relationship between God’s justice and human action, with surprising resonances in the Pacific today.

08 Tuesday Feb 2022

Posted in climate change, sermon

Tags

preached at St Paul’s Hills Road, Cambridge

Watch this online https://www.twitch.tv/videos/1288961155?t=0h37m15s

Let us pray.

Dear God, may these spoken words be faithful to the written word and lead us to the living Word, Jesus Christ our Lord.

When I was invited to preach here this Sunday, I realized that it would be Waitangi Day back home in New Zealand. This public holiday commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in Waitangi, New Zealand on 6 February 1840 between representatives of her Majesty, Queen Victoria, and numerous Maori chiefs.

It is a Treaty that remains controversial due to it having radically different interpretations. Did the Treaty intend to prevent, slow, or permit the colonization of New Zealand? Did the parties to the Treaty understand what they were doing? Were the intentions of the parties stated honestly at the time? And since then, to what extent has the Treaty been breached by the Crown and successive governments? Without agreement on how such questions are answered, the Treaty, will, I suspect, remain controversial for many years to come.

A part of the Treaty protects the taonga or treasures of the Maori people including their culture. This includes the environment and their way of life dependent on the resources of the land. Nevertheless, colonization transformed the ecology and the lives of the indigenous Maori people, who suffered population loss through disease and war, and land loss through the government seizing their land, pushing many of the remaining Maori people far from their ancestral lands into cities.

New Zealand is a settler colony. My ancestors traveled to New Zealand from Scotland and England seeking a better life in New Zealand. With other settlers they transformed the forested landscape into what they thought was more productive land use – pasture for the production of wool and protein products for Great Britain. That was New Zealand’s role in the British Empire, and then Commonwealth, until Britain entered the Common Market in the 1970s.

A major but often forgotten factor in the colonization of New Zealand was ecological colonization; the turning of New Zealand landscape into a new British landscape. In many ways, the settlers wished to make this antipodean land look and feel and smell like ‘home’. Yet, the Treaty of Waitangi was supposed to protect Maori from this devastation of their way of life and the dispossession of their lands.

From one perspective, the history of New Zealand can read like Deuteronomy 7 – go to the promised land and occupy it driving the people out.

To this day, there are New Zealanders who wish that their ancestors had taken the advice of Deuteronomy 7:2 “Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy.” For settlers, the Treaty of Waitangi stands in the way of progress based on the completion of the settler colonial agenda of white supremacist domination of both land and people.

For many Maori, the Treaty is a sacred covenant. This view is based on the fact that it was Anglican and Methodist missionaries who translated the Treaty of Waitangi into the Maori language. It was missionaries and their recent Maori converts who convinced the Maori to sign this Treaty with Queen Victoria, Supreme Governor of the Church of England. For these reasons and more, Maori believed that the Treaty is a sacred covenant.

The Treaty is still viewed in this way, and is interpreted to provide a way of protecting their land and environment, restoring their dignity, and being able to practice their culture. Yet, almost since it was signed, the Treaty was dishonored by the successive governments, leaving Maori in a position as if there had been no covenant at all.

What has been the outcome of settler colonization for the ecology of New Zealand? Quite simply, the quest to reproduce England in the antipodes has been an ecological disaster. Take, for instance, the introduction of hedgehogs into New Zealand. Last year The Guardian reported on a study from New Zealand on how the hedgehog, far from being the lovable Mrs Tiggy Winkle of Beatrix Potter’s tales, was a killing machine.

Hedgehogs were introduced into New Zealand to remind settlers of the gardens of home and to “contribute to the pleasure and profit of the inhabitants”. But with no predator, the hedgehog thrived and there are now more hedgehogs in New Zealand than in Britain. Little known is how destructive hedgehogs are to native wildlife, eating the eggs of endangered birds, lizards, and insects.

This is just one example of the ecological imperialism of settlers in New Zealand. While this might seem distant from Cambridge in time and space, there are lessons here for all of us.

Our ecological crisis is largely the result of human activity that seeks to remake the world for the pleasure and profit of its inhabitants. This was not something only done to colonized lands, this approach to the altering of landscapes is a part of human history. With industrialization and a larger population, we have taken this to a new level. And we should not deceive ourselves that things done for our “pleasure and profit” will be beneficial to other human or creatures, based as it is on our distorted desires.

In light of this, our Hosea reading provides a theme that needs much greater emphasis today: the land suffers because of human sinfulness. The land mourns and the creatures languish or even perish.

Our climate crises and the current mass extinction events are testimony that something is very wrong in our world. Interpreted through such prophetic texts we can only conclude that human wickedness is to blame for the state of our environment.

Ours are not straightforward ecological sins, such as not recycling or chopping down trees to make pasture for sheep. No. There is more to it than that.

If we pay close attention to the prophet, the sins mentioned by Hosea are all relational sins done against other people. Swearing, lying, murder, stealing, adultery are all things we do to do someone or in disregard to someone.

Telling a lie might not seem, on the face of it, an ecological sin. But when we learn that corporations and governments have been lying to us for years about the effects of fossil fuels, then it is easier to see.

Adultery? Is it any surprise that if we can discard our spouse for another, that we have no difficulty believing it is OK to discard tons of waste from our cities every day.

Murder? In Colombia, South America, 65 land and environmental defenders were murdered in 2020 alone. That’s more than one a week.

And in the case of colonization, “bloodshed follows bloodshed”. The murder of indigenous people to seize land for development continues to cause untold harm to people and land, such as in West Papua, site of the Grasberg mine the world’s largest copper and gold mine on land stolen from the West Papua with the approval of the world’s major powers.

We know of the state of the climate: global warming is real, the climate is changing and politicians seem captured by agendas other than working for the common good, which has to include providing a climate in which human and other species loved by God in their right, can flourish.

Actions by individuals do not seem to be doing enough in the face of states and corporations wishing to increase their power and control in our capitalist society. Direct action by communities has a lot of potential, but activists have not been able to match shifts in public thinking on climate change with commensurate meaningful action on climate change.

Can humans save themselves from climate change? Where is God in all this? Must we simply sit with Hosea’s condemnation?

Tomorrow night I begin teaching a short online course on “Preaching the Good News into the Climate Crisis”. What is this good news you may ask? I have been wondering that myself.

One answer is that there are no answers – yet. Some might say that we are now living in a new era – the Anthropocene. With our question and answers, including those from the Bible, predating this new era, it is argued that they cannot save us. We need new ideas for our new time. Must we, therefore, wait on a new savior, one we have not encountered before?

Another approach is to say that to live by faith in Jesus is to trust in God that God has already given the answer to such questions.

Let’s turn briefly to our gospel reading (the Lectionary Gospel reading for today) to see a different understanding of God’s ecology and economy. The focus here is on the miracle of the plentiful fish. With Jesus in control, the world is a place of life, abundance and not scarcity.

Whereas the fish in Hosea are swept away or taken away because of human sin, in Luke we see the nets straining under the weight of abundance.

Sin leads to fish being scarce; obedience to Christ leads to fish being plentiful.

Today, some might pause here to ponder the meaning of creation serving our needs and the problem of overfishing in our oceans, but my point is different one. We are called to obedience to Jesus and to be his followers.

Simon, the fisherman, trusted God, even before the miracle of the fish. His obedience and trust in Christ transforms him and his friends.

Jesus is calling us to follow him as he did Simon – even to the point of leaving the world one knows behind and to enter into an unknowable journey with Christ. For us facing an unpredictable and uncertain future as we go deeper into a climate crisis such a radical change of direction may be what is needed.

If God is calling us to do that, to leave behind our economy and way of life (even at its most profitable point, as it was for Simon), we must have faith that Christ will bring an even greater abundance as we shift our desires to align with his.

This requires great faith in God that through the power of the Holy Spirit we can sift our scriptures and traditions to find resources for the journey ahead to an ecological way of life in harmony with other creatures and each other.

In the age to come, we must have hope to believe that there is hope.

Despite the long, brutally harsh condemnation of Hosea, the prophetic voice is not just one of condemnation. The prophetic is also a call back to repentance and faithfulness and harmony between God and his people, people with each other, and with creation. This message is also Christ’s gospel for our climate crisis.

I shall end with the vision of Hosea chapter 6:

“Come, let us return to the Lord.

He has torn us to pieces

but he will heal us;

he has injured us

but he will bind up our wounds.

After two days he will revive us;

on the third day he will restore us,

that we may live in his presence.

Let us acknowledge the Lord;

let us press on to acknowledge him.

As surely as the sun rises,

he will appear;

he will come to us like the winter rains,

like the spring rains that water the earth.”

Amen.

31 Sunday Oct 2021

Posted in climate change

Tags

With COP26 kicking off in Glasgow here are some of my writings of climate change (also click on the ‘climate change‘ tag for this blog.

Davis, Richard A. 2015. ‘The Rainbow Covenant, Climate Change, and Noah’s Exile’. The Pacific Journal of Theology, Series II, , no. 54: 37–44. https://archive.org/details/pacificjournaltheology_II_54_2015/page/36/mode/2up

———. 2015b. ‘The Politics of Public Wisdom—Proverbs 1:20-33 (Richard Davis)’. Political Theology Network. 12 September 2015. https://politicaltheology.com/the-politics-of-public-wisdom-proverbs-120-33/.

———. 2016. ‘The Politics of the City and the Sea—Revelation 21:1-6 (Richard Davis)’. Political Theology Network. 18 April 2016. https://politicaltheology.com/the-politics-of-the-city-and-the-sea-revelation-211-6/.

———. 2017. ‘The Politics of God’s Reconciliation—Romans 5:1-11 (Richard Davis)’. Political Theology Network. 13 March 2017. https://politicaltheology.com/the-politics-of-gods-reconciliation-romans-51-11-richard-davis/.

———. 2020. ‘Climate Justice and God’s Justice in the Pacific: Climate Change Adaptation and Martin Luther’. In Climate Change Adaptation in the Pacific Islands: Opportunities for Faith-Engaged Approaches, edited by Johannes M. Luetz and Patrick D. Nunn, 99–113. Climate Change Management Series. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67602-5_6.

What can Methodists contribute to the issue of climate change from both theological and activist points of view as we approach the COP 26 meeting in Glasgow? Host Dr Richard A. Davis, panelists:

From https://www.wesley.cam.ac.uk/centre-for-faith-in-public-life/centre-events/

20 Wednesday Oct 2021

Posted in anarchism, Christian Anarchism

Testimony forms a major genre of Christian Anarchist writings. Here is an example of this type of writing from Ross E Martinie Eiler writing for Plain Words, Anarchist Counter-Information in Bloomington, Indiana.

https://archive.org/details/ZineArchive/Plain-Words-6/page/n9/mode/2up

19 Tuesday Oct 2021

Posted in anarchism, Christian Anarchism

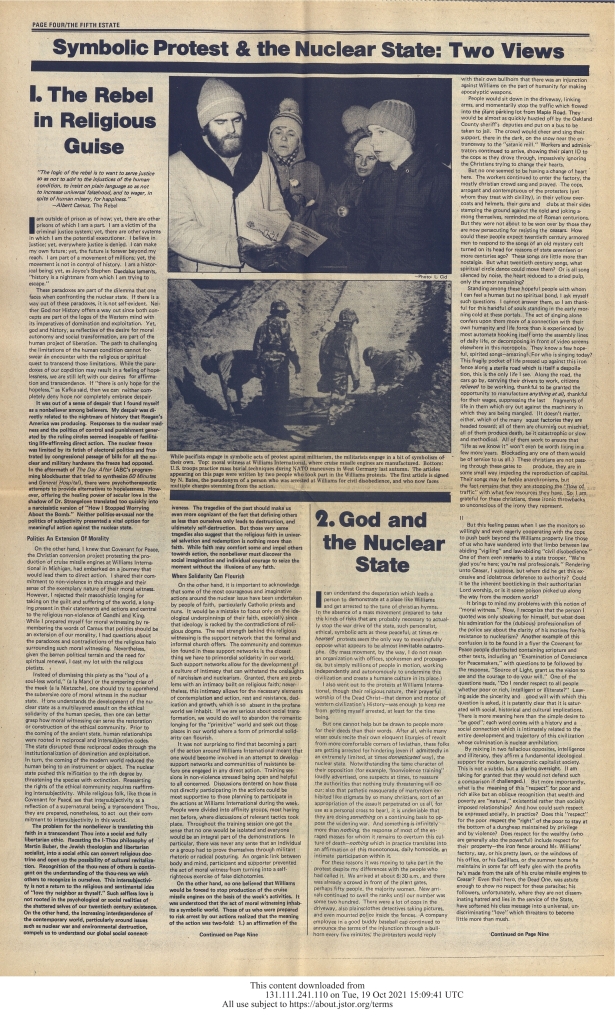

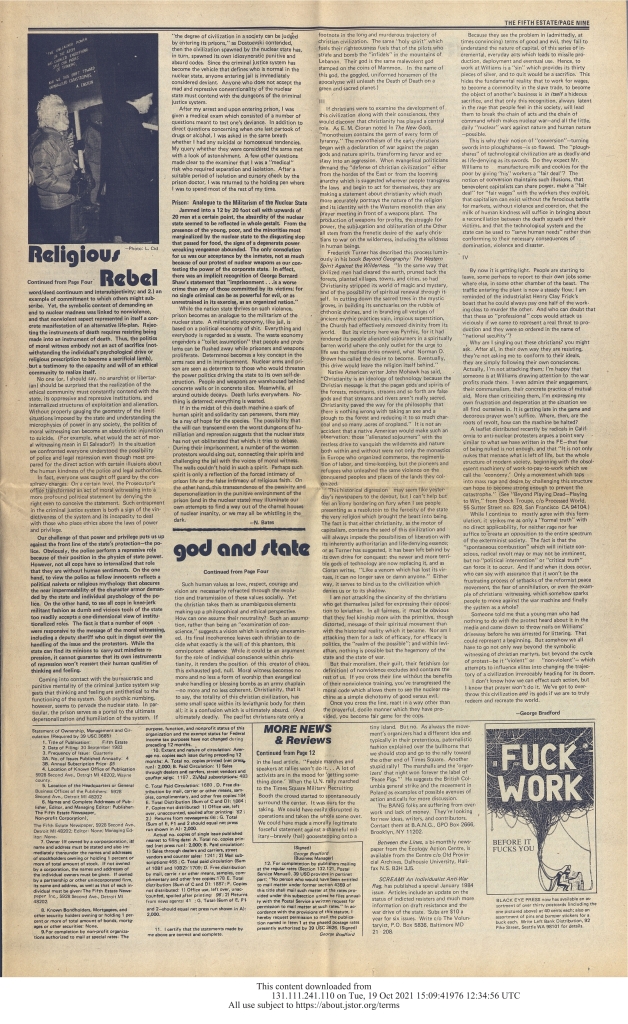

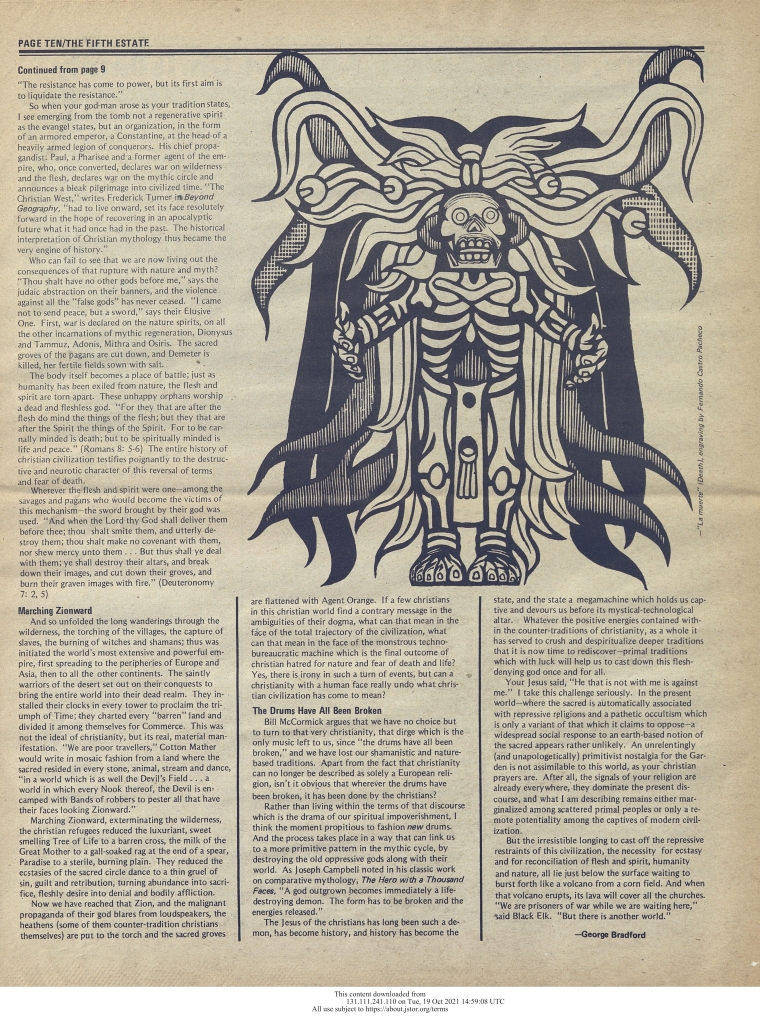

Here’s some links to and images of a series of articles and comments and responses from the radical journal Fifth Estate about religiously-inspired civil disobedience and Christian anarchism.

It begins in the Winter 1984 edition (Vol. 18, No. 4, #314) in an article titled ‘Symbolic Protest & the Nuclear State: Two Views’ by N. Bates and George Bradford (pages 4, 9)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/community.28036639.pdf

Replies then came in the Summer 1984 issue (Vol. 19, No. 2, #316) from Bill Kellerman and Bill McCormick (pages 8, 22) and a counter reply by George Bradford (pages 9, 10) titled ‘Anarchy & Christianity: An Exchange’.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/community.28036641.pdf

30 Thursday Sep 2021

Posted in Uncategorized

The world planners gather.

The young men mixed red blood with blue water

And windy sands covered shattered helmets.

The old men confer with figures

And refashion their empires.

They seek a solution; they have it,

And they know it not.

Once when the world was younger

Some nineteen hundred years,

A quiet man walked the Judean hills

And along Galilee’s shore;

Then men left their nets.

And he spoke to the people

On a mountain with loaves and fishes,

And he entered the city on a burro

And they hailed him emperor—

And they nailed him to a cross.

“The Kingdom of God is among you.”

They worshiped his teaching

But were afraid to live it.

The world planners gather,

They seek a solution; they have it,

And they know it not.

Arvel Steece, “World Planners,” Christian Century, March 20, 1946.

SOURCE: https://archive.org/details/sermononmount0000jord/page/94/mode/2up